Permissions Worth Getting Excited About¶

Permissions. Doesn’t the very subject set your heart racing?

No?

Well, me neither; normally. But, rather to my surprise, my thesis today is that one of the most revolutionary and remarkable features of FluidDB is its permissions system, and that this, more than anything else, explains why it has a shot at blowing apart web applications and social data.

I accept it’s an unlikely claim. But let’s see if I can make a case.

WTF?¶

If you ever hear Terry talk about FluidDB, or read his stuff, the guy speaks in riddles. One minute he sounds like Richard Stallman, banging on about freedom and how when he rules the world no one will have to ask permission to write data, no one will own objects, everything will be shared and social and anarchic and messy and we’ll all be able to do exactly what we want. He even calls FluidDB the database with the heart of a wiki, whatever that’s supposed to mean. And the very next next minute, he’s talking about how at the heart of FluidDB lies a really strong permissions system that allows us to control exactly what goes in FluidDB.

The guy’s clearly schizophrenic, if not paranoid delusional. Right?

In Defence of Terry¶

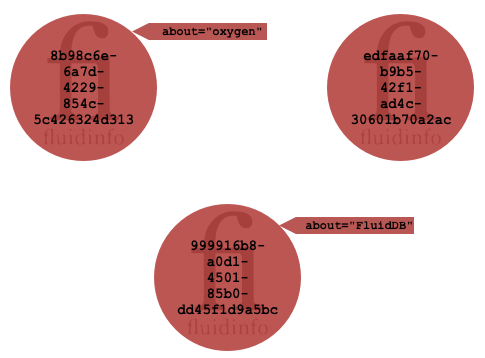

FluidDB is a remarkably simple conception. At its heart, it’s just a collection of initially empty containers to which we can attach tags. In best computer-science tradition, we call the containers objects and they really are 100% shared.

If you can find an object, you can tag it . . . and so can anyone else.

As you can see, the objects all have rather long, individual identifiers—actually 128-bit numbers sometimes known as UUIDs [1]. Some objects also have a second identifier, known as the about tag. About tags are unique and never change, so there can only be one object in FluidDB whose about tag is set to the (exact) string oxygen, though there can be any number with no about tag.

So objects are not owned, but shared, and once created, are never destroyed [2].

So one half of the claim is good: objects are shared, and anyone can tag them with whatever they like. Where do all the permissions and control come in?

Tags and Values¶

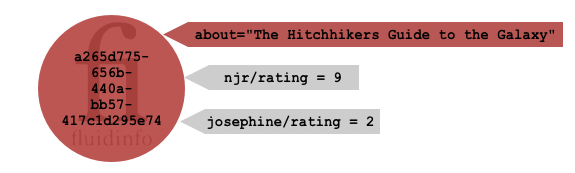

When we say that anyone can write to any objects in the system, that’s true. Anyone can stick any tag they like onto any object they can find [3]. The tag has a name, such rating or colour or Ulysses and may have a value—such as 7, or interesting or a picture of some leaves. Like this:

The only restriction your tag names all start with your FluidDB username. For example, my FluidDB username is njr, so my tag names start with njr/. So I can have njr/rating, njr/colour njr/Ulysses, or anything else I like. And you, Josephine, can have tags called josephine/rating, josephine/colour (or even josephine/color, if you’re that way inclined) and so on.

Placing tags on the same object in FluidDB is, of course, a way of relating them, but that isn’t the focus of this article.

Permissions¶

So finally, we come to the bit.

By default, I can only create and set tags starting njr, but can read any tags, while Josephine, naturally enough, can only create and set tags starting josephine. Unlike objects, tags are owned.

But there is a permissions system that means that I, as the owner of the owner of tags starting njr, can control exactly what Josephine can do with my tags and vice versa.

So if I want to, I can hide my ratings from Josephine, but let her see my colours. Or I can hide them from everyone except Josephine and Terry.

Slightly more unusually, I can also choose to allow some, or even all other users to write some of my tags if I like. For example, I might decide that I trust Terry enough to allow him to set some of my tags.

This ability to control who can do what extends not only to users, but to applications as well. So suppose someone writes an application called Read-Planner that allows people to tag any book they run across on the web (or anywhere, in fact) with a to-read tag. If I want to use this application, I don’t have to give it my password or open up access to all the rights that I have: I can simply give Read-Planner the ability to create to-read tags for me. And if at some point I become unhappy with it, of course I can revoke that permission. I don’t even need something like OAuth: I can just do it.

Even better, I can also choose to allow other applications whatever form of access to my to-read tags I want—maybe read only, or maybe some of them have write access too. It’s up to me.

And this is why we think FluidDB has the potential to be so revolutionary: it is truly social, while leaving each user firmly in control of his or her data.

New Rules for Web Applications¶

At the moment, any of us who use web applications tend to spend a lot of time and effort populating application databases to make them useful to us. But when we do so, we tend to lose control of our data. They go into a private database schema, and what access we have to that depends entirely on what the application allows us to do. Sometimes there are reasonable ways to get the data back out (some kind of an XML dump perhaps), sometimes not. But always the application is in control. And linking data across applications is, in general, somewhere between hard and impossible.

FluidDB can change all that by leaving the user in control of his or her data, granting the application only such permissions as necessary or desired, and ensuring that the user retains flexability and control.

Now obviously, this only works if applications agree to work with data in this way, and equally obviously, a lot of them are going to be extremely reluctant to do so. After all, in the well-worn phrase, information is power. So it’s more than possible that far from embracing the openness and intrinsic cross-application, cross-user interoperability championed and facilitated by FluidDB, many applications will seek to hold onto the data. We fully expect this.

But we also expect that there will be some applications, perhaps new ones, perhaps small ones initially, that will embrace the idea. And over time, a movement can grow, perceptions can change, and maybe in ten years time the idea of an application owning and controlling your data will seems as antiquated as the notion that you shouldn’t be allowed to see your own medical records.

A Tiny Bit of Detail¶

I’ll close by talking in slightly more detail about the way the permissions system in FluidDB operates. Further articles will go into the gory details.

Briefly, you can set permissions for each group of tags sharing a name. [4] So for example, if I use a rating tag, I can control exactly who can read, change and create this njr/ratings tag. And I can control each of those aspects independently. [5]

Similarly, if I choose to use names that contain slashes, like maybe njr/book/rating and njr/book/own I can choose control who can do what at the level of a stem like njr/rating if I choose. So I could allow some book applications, or a bookish friends, to manipulate my book tags, maybe even creating new ones for me, but not my other tags (especially not my njr/private ones!)

Conclusion¶

Unlikely as it sounds, one of the key innovations in FluidDB is its combining a completely shared set of information containers (the objects) with the ability for users to tightly control, at a granular level, precisely who can read, write and create the tags used to store information on those objects. This applies not only to users, but also to applications, giving a simple way for users to grant applications broad or narrow access to read or manipulate some or all of their data while, ultimately retaining complete control of it.

In FluidDB, you never need to ask permission to write to an object, but you always need permission to use someone else’s tags.

It’s a powerful combination.

| [1] | So-called Universal Unique Identifiers. |

| [2] | In fact, we sometimes like to say that objects for every possible about tag already exist, in rather the same way that Plato believed that all numbers and other mathematical objects existed in perpetuity in what we now call his platonic universe. It’s simply that we only bother to allocate storage for objects with any particular about tag when someone actually wants to use it. |

| [3] | If it doesn’t have an about tag, an object might be very hard to find, essentially requiring you to guess a 128-bit number. But it doesn’t really matter, as we’ll see. |

| [4] | We sometimes call the set of tags having, or potentially having a particular name (like njr/rating) as an abstract tag. We can think of the (concrete) tags that we actually attach to FluidDB objects as concrete instantiation of a canonical, abstract, platonic, master tag of the same name. |

| [5] | There are actually more than three aspects I can control, but this the essence of it. |